Things That Look Like Opposites May Cohere

- Democracy Chain

- Nov 19, 2025

- 5 min read

by Margaret Hawkins

As if Americans weren’t already polarized by the messes we’re entrenched in, Charlie Kirk’s assassination took it to a new level. Politicians and religious leaders spoke about rising above our differences, but that’s not at all what happened. If anything, trash talking intensified. Everybody doubled down on their side.

What happened: A twenty-two-year-old climbed onto a rooftop with his grandpa’s decades-old military rifle and aimed at an incendiary right-wing pundit speaking to a crowd of college kids. He dropped the speaker with one shot to the neck. On camera. The ensuing public discourse focused not on gun control or better mental health care — we seem to have abandoned those ideals as even possible — but about whether it’s OK to mourn the killing of someone you disagree with. Whether it’s OK to commit violence against someone whose ideas you consider repugnant. And if Kirk isn’t your flashpoint, pick another. On either side. Two weeks after Kirk’s murder, the beachfront house of a liberal South Carolina circuit court judge and her Democratic ex-senator husband was blown up and burned to the ground. And it’s not just here and not just about politics. In London, people were shot coming out of a synagogue on Yom Kippur. Name your own horrible adventure. Everywhere, people are withdrawing to insular pods of self-righteous certainty.

Political violence is terrifying no matter where it originates. For many on the left, especially those for whom the peace sign was once a universal greeting, it’s also disorienting. The recent trend in blowing up and burning down public servants’ houses — think Josh Shapiro, the sitting Governor of Pennsylvania — proves that the problem goes deeper than guns. The quaint idea that being on the left means favoring kindness, or at least tolerance, has all but vanished. What seems undeniable now is that meanness and violence and philosophical rigidity are not only the norm, they’re the ideal the emanates from the very core of the Trump regime and spreads from there like an invasive weed.

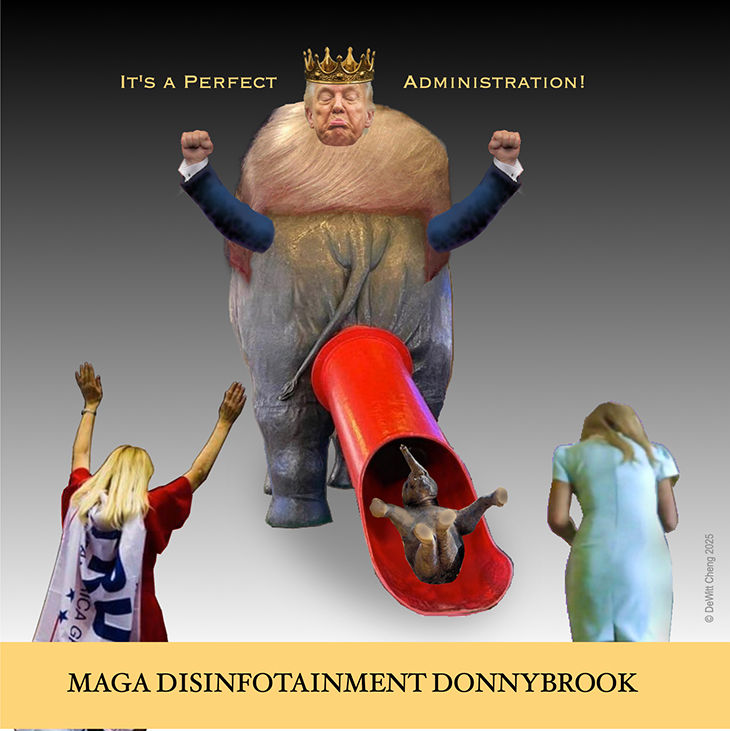

Fortunately, that is not nearly always the case. The orderly No Kings Day protests of October 18th proved the left can be peaceful, even en masse, even when goaded with a coarse and absurd meme showing the president wearing a crown and dropping feces bombs on a crowd of protestors. But day-to- day discourse between disagreeing parties has continued to deteriorate. The self-righteousness of the left has calcified into something even colder than anger: contempt. This rigid certainty may be the ultimate result of the very principles the country was built on — self-reliance, individualism, exceptionalism. For better and worse, this is how we’ve gotten where we are.

To look at it from another perspective, consider British psychiatrist Dr. Iain McGilchrist’s groundbreaking brain research. In “The Matter with Things” (2021, Perspectiva Press) he argues that his study of brain hemisphere asymmetry in schizophrenics reveals a parallel disintegration in Western society. Societies that begin with flexibility, imagination, and creativity lose these qualities as they become more hierarchical and less wholistic. He says this decline mimics the way schizophrenia affects the brain, causing it to perceive the world in pieces rather than as a whole in which unlike parts can still fit together. He refers to the Western world’s current state as one in which “people aren’t trained to think critically about their own opinions.” We only see the small parts of the world we’re comfortable seeing and fail to notice, he says, that “things that look like opposites may cohere.”

A few years ago I started getting emails from something or someone that calls itself DeepDharma. I didn’t recognize the name and sometimes weeks passed without a message. Then a couple would show up in close proximity. They appeared to be condensed principles of Zen Buddhism and they never asked for money or for me to attend meetings or events, or do anything at all. No ads, no product endorsements. No music, memes, jokes or barbs. No political endorsements. Just thoughts, often quite brief. When I finally started to open and read them, they always felt oddly pertinent.

The messages come in appetizing little thought-bits, sometimes as short as a sentence, perfectly suited to the shrunken attention span most of us, increasingly, suffer from. Sometimes they end with a surprising twist, like a koan. They appear, I read them, I forward some to a childhood friend, then let them subside into the vast cloud of email never to be looked at again.

But sometimes the ideas linger. Maybe that’s because lately the messages that stick in my head are the best reply I’ve heard to what’s going on in the world. Maybe they are the only remedy. Allow me to share a few; I believe that’s the intention.

A recent one was titled “Arrogance.” It ended this way:

We are not inferior to anyone

We are not superior to anyone

We are not equal to everyone.

Easily understood, until that last tricky line alluding to individuality.

Another line that stuck in my mind:

We are not punished for our anger. We are punished by our anger.

Dharma is a term in Buddhism and Hinduism that refers to the nature of reality. I like the simplicity of that definition. Simple, not easy.

Here’s my favorite, titled “Believe Only This.” It lists the 10 sources of information the Buddha recommends dismissing, an idea that seems strikingly modern and proves that disinformation is an age-old problem. It’s the best advice I’ve seen for how to approach our current news cycles. Roughly categorizable as “religious,” the ideas put forth in DeepDharma are the opposite of dogma. In fact, they support critical thinking, a practice that seems to have gone out of fashion. Here is the post:

“Believe Only This”

The Buddha provides ten specific sources that should not be used to accept a specific teaching as true, without further verification:

Oral history

Tradition

News sources

Scriptures or other official texts

Logical reasoning

Philosophical reasoning

Common sense

One’s own opinions

Authorities or experts

One’s own teacher

Instead, the Buddha says, only when one personally knows that a certain teaching is skillful, blameless, praiseworthy, and conducive to happiness, and that it is praised by the wise, should one then accept it as true and practice it.

The emphasis remains on one's personal knowledge of whether a particular teaching reduces or eliminates the defilements of greed, hatred and ignorance, or increases them, in which case it should be rejected.

Margaret Hawkins is a writer, critic and educator. Her books include “Lydia’s Party” (2015), “How We Got Barb Back” (2011) a memoir about family mental illness, and others. She wrote a column about art for the Chicago Sun-Times, was Chicago correspondent for ARTnews, and has written for a number of other publications including The New York Times, the Chicago Tribune, Art & Antiques and Fabrik. She teaches writing at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and Loyola University.

Comments